Jack’s Story

Jack Charles – Aboriginal Elder, film and stage actor, potter, indigenous activist and former cat burglar – is a brilliant storyteller. His gift of writing from the heart, provided him with cachet and respect when imprisoned. He would sit down with illiterate inmates, discuss what was required and then pen deeply felt letters to the prisoner’s loved ones.

Jack’s life was derailed when he was stolen at the age of four months from his mother, Blanchie Charles, and made a ward of the state. Jack was her first baby and all eleven of Blanchie’s babies were forcibly taken from her.

He writes in, Born Again Blakfella, that had his mother known he was, ‘subjected to repeated beatings, sexual abuse and desperate loneliness’, it probably would have destroyed her.

‘They say when a child is born, so is a mother. That so many First Nations Families, women in particular, were not afforded the basic human right of raising their own children is deplorable.’

Jack Charles has a beautiful voice: mellifluous, resonant, deep and compelling. His voice was created by his favourite teacher who provided Jack with elocution lessons. It was a gift. But at the Salvation Army Box Hill Boy’s Home he wasn’t encouraged to be academic. All Jack wanted was the same opportunities as the non-indigenous boys.

However, his teacher’s efforts paid off, ‘I was introduced to famous speeches and had a natural talent for memorising and reciting them, which held me in good stead for my future acting days … Speeches like the Gettysburg Address were moving to me … I liked the sound of them.’

Jack was imprisoned twenty-two times, mostly for his burgs –burglaries. It surprised him that Melbourne’s rich kept stashes of cash all over the house. Some houses were so financially rewarding that he revisited them.

‘There was a large double mansion I did over in Hawthorn. Actually, I did over this joint a few times, because the owners always left wads of cash in the cutlery drawer … Each time I went back, there’d be a fresh stash of cash in the cutlery drawer.’

Having learnt how to throw clay pots on a wheel and operate a drying kiln, he efficiently ran the pottery studio at Castlemaine’s prison.

‘I may have been a diminutive figure, but I ran those pottery workshops with a sense of Aboriginal law. Everybody followed my rules and respected the place as a hub of peace and creativity.’

Jack Charles is probably best known in Australia as a screen and stage actor. He appeared onstage at the Sydney Opera House with musician Archie Roach in 2017. In 2014 his powerful one-man stage show, Jack Charles vs The Crown played at the Barbican in London.

The film Bastardy introduced him to a wide audience. Bastardy is a documentary film about seven years in Jack’s life.

He admits it’s hard to watch, ‘In the doco, film maker, director and producer Amiel Courtin-Wilson captured my burgs, jail time, heroin addiction and homelessness, as well as my road to redemption.’

Bastardy opened at the International Film Festival with two premiere screenings. It was an instant success and many folk were keen to talk to Jack. An older couple approached him to tell him how they’d enjoyed the film and admired it greatly. The woman tentatively mentioned that their Camberwell house had been robbed thirty years ago. The implication being that Jack might have been the burglar, as that area had been his favourite hunting ground. Jack handled it well and all three, ‘cracked up and had a good ol’ laugh’.

Born-again Blakfella is a really powerful book and Jack Charles tells his story in a gutsy, honest manner. Parts of the autobiography are hard to read because he endured astonishing brutality and unkindness. However, everything balances out as Jack’s mischievous nature is apparent throughout the book. He tells several witty stories about how he became an accomplished, sought after actor while pursuing his bread-and-butter career as a successful cat burglar. Several times his cheeky wit and erudite turn of phrase made me laugh out loud.

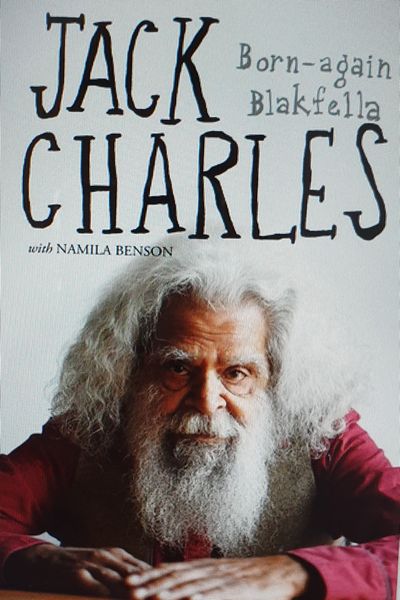

Photo: cover of Born-again Blakfella by Jack Charles (with Namila Benson). Published by Penguin Books Australia August 2019.